Alice Rohrwacher’s new, prize-winning film La Chimera unfolds in Tuscia –the northern corner of Lazio bordering Tuscany and Umbria, where I happen to live most of the year. It’s a place out of time, which sees few tourists, with tiny villages teetering on the edges of steep ravines. Once the center of Etruscan culture, the whole area is riddled with Etruscan tombs, some still undiscovered.

Rohrwacher’s film, set in the 1980s, centers upon a group of tombaroli, tomb hunters who make their living illegally scavenging Etruscan tombs for priceless, ancient artifacts. While many tombaroli were motivated both by a love of adventure and a need for cash – others were drawn to the ghostly atmosphere of the tombs and the Etruscans’ spiritual legacy. Local superstitions claim that Etruscan ruins are unlucky places, but many native Tuscians feel a strong connection to this mysterious people.

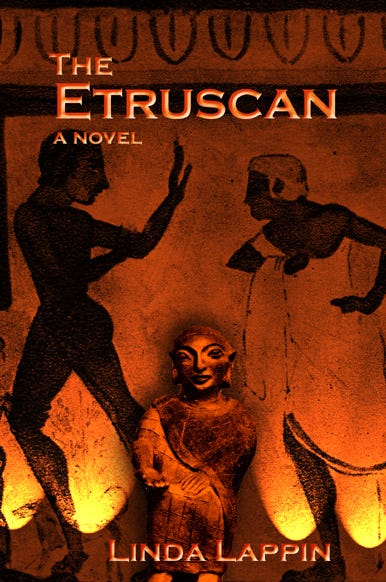

The English tomb hunter in La Chimera played by Josh O’Connor who uses his dowsing skills to locate tombs isn’t performing a magical act, but simply practicing an art known to rural cultures the world over. In addition to finding water, dowsers can find minerals, iron tools or coins, buried in the earth, and there are many cases of archaeologists teaming up with dowsers to search for sites. I refer to this practice in my novel The Etruscan, originally published in 2004, and scheduled for reissue in fall 2024. Like Rohrwacher’s film, my novel celebrates the wild landscape, eerie atmosphere, and traditions of Tuscia.

Among the sources Rohrwacher credits for inspiration is D.H. Lawrence’s seminal work: Etruscan Places. Lawrence's approach to the Etruscans was highly personal and unscientific, yet his posthumous book, published in 1932, has shaped modern readers' ideas of this vanished people more than any other text.

The Genesis of Etruscan Places

Near the end of his life, D.H. Lawrence returned to Italy in 1927 after a soul-searching journey through Mexico, the American Southwest, Ceylon, Australia, and New Zealand. Gravely ill with tuberculosis, unaware of how little time he had left (he died in 1930 at the age of 44), Lawrence sought an ideal land where he might flourish as a "whole man alive" and find an antidote for the alienation of industrialized society denounced in his fiction, particularly in Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

Lawrence's last pilgrimage led him to the Etruscan ruins north of Rome. His idea was to write a travel book about the twelve great cities of Etruscan civilization. Lawrence rejected the scholarly views of his era: that Etruscans were morally inferior to the ancient Romans, a view promulgated by Italy’s Fascist regime who identified with the military-minded Romans.

Instead, in the Etruscans, Lawrence found a life-affirming culture which exalted the pleasures of the body and viewed death as a journey towards renewal. He also believed that Etruscan culture was based on equality between the sexes, and this idea influenced his portrayal of the relationship between Connie and Mellors in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, his last and best-known novel. For Lawerence, Etruscan culture was infused with the joy of being and and informed by a superior level of consciousness.

“To the Etruscan, all was alive, the whole universe lived, and the business of man was to live amid it all. He had to draw life into himself , out of the wandering, huge vitalities of the world.” … [The Lucumones (ie high priests) were] The life-bringers and the death-guides. But they set guards at the gates of life and death. They keep secrets and safeguard the way.” —D.H.L.

Traveling on foot and by mule cart, Lawrence explored Etruscan territory. He visited the frescoed tombs of Tarquinia and the rougher rock tombs of Cerveteri, as well as the sites of Vulci and Volterra. The tomb sites Lawrence described are easy to visit today, well-connected to Rome and Florence by trains and buses. In Vulci and Volterra, museums offer informative displays on Etruscan history. In the frescoes of Tarquinia, pipers play on as red-skinned dancers perform to the delight of thousands of tourists every year. And copies of Etruscan Places are for sale everywhere.

The mystery Lawrence relished may best be found off the tourist track in the rock tombs carved along the ravines throughout Tuscia, as depicted in Rohrwacher’s La Chimera, where there are still tombs to be discovered. As late as February 2024, a monumental tomb was discovered in the San Giuliano necropolis.The landscape in Rohrwacher’s film seems semi-abandoned, forlorn, enticing. If you visit, you will find she has captured its soul of place.

I have spent many years exploring lesser known areas out in the Tuscia countryside, off the main road. Wandering waist high in weeds across a tumulus, you’ll find tall doorways leading into chambers hollowed out in the rock along the edge of a cliff. Often on the back wall, a fake door is either carved or painted. Lawrence believed this was the door of the soul through which the spirits of the dead passed on to the afterlife. A barrier for the body but not for the imagination.

Etruscan Places has been read as Lawrence’s attempt to reconcile himself with his own mortality. He was convinced that for the Etruscans, death was a continuing celebration of life, or so he learned from studying their tomb art. “What one wants,” he wrote in the closing pages of Etruscan Places, is not a lesson about the Etruscans, but direct “contact.” It is this contact which he tried to pass on to us. Rohrwacher has seized the thread.

My own explorations of Tuscia

Lawrence’s vision of the Etruscans in Etruscan Places is among the chief inspirations for my novel, The Etruscan, set in the 1920s, in the era of Lawrence’s visit here. The heroine, Harriet Sackett, a feminist photographer, comes toTuscia to photograph Etruscan tombs and finds herself entangled with count Federigo del Re, occultist and self-proclaimed Etruscan spirit. It’s the story of an irresistible attraction between a modern, advanced woman and an archaic-minded, patriarchal male, between America and Italy, and ultimately, between the worlds they embody: the temporal and the timeless. Like the protagonist of La Chimera, Federigo del Re is a refined tombarolo with a gift for dowsing and much more.

While working on my novel, I lived in a farmhouse outside the gates of an old Etruscan town, with windows overlooking a gorge where dozens of tombs have been hollowed out of the rock face. You cannot live in a such a place for long without unconsciously absorbing its mystique. Researching the background for my novel, I soon learned that it was quite common for local people, from aristocrats to farmers, to believe they were somehow in touch with the vanished Etruscans.

I met dowsers and healers who trace their occult powers back to the Etruscans. I met a controversial scholar who has dedicated a lifetime to studying step pyramids and altars in the woods north of Rome that remain unexplained by the academe. I met a geologist who showed me a hidden spot in the woods where strange magnetic phenomena occur, a tombarolo who invited me to explore with him, a paranormal researcher who has recorded strange echoes in caves, and a painter who studies the lay of the land from a balloon.

I met a chef who cooked me dishes he believed were surely of Etruscan origin and the author of a cookbook whose grandmother ran the trattoria where Lawrence liked to dine. I met a woman who leads tours to a secret place where witches gathered in the middle ages. A countess unveiled for me her secret collection of Etruscan artefacts illegally assembled by her grandfather. I met a designer who creates hats based on Etruscan designs and a sculptor who peoples his life with terracotta sphinxes of Etruscan inspiration. I listened to folk tales and dreams recounted, all telling of the underworld, and like Harriet Sackett , I sat for hours in dank tombs, pondering the door of the soul separating this world from the next. The fruits of all this research and reflection are to be found in my novel The Etruscan, in which I hope readers will discover the same fascination that I have found in the spirit of the Tuscia.

The Etruscan was originally published in July 2004, by Wynkin deWorde, a small literary press in Galway, Ireland. The 2024 revised edition from Pleasure Boat Studio will be the first paperback edition ever. Kirkus noted: “Haunting…vivid…Entrancing.”

A Page from The Etruscan

The road to the tombs skirted a field of shriveled sunflowers, an army of nodding heads on stalks, bowed and blackened, awaiting harvest. There were no houses out this way, only wide expanses of tawny stubble, alternating with strips of freshly ploughed clay. Here and there on a hilltop, a dead oak or cypress punctuated the empty sky where hungry crows swooped low.

Grazing in the quiet meadows were flocks of dirty sheep. Their bells tinkled as they turned their heads to stare at me. A solitary traveler on the road, an alien by local standards: a tallish woman, no longer young, wearing a pair of moleskin trousers and rubber boots; a rucksack swinging on my shoulders. The black felt hat pulled low over my forehead concealed my cropped blonde hair. When working or traveling, I always dress in men’s clothes. To those placid sheep I probably looked like a walking scarecrow.

In the distance, beyond the brown hills, I could just see the tip of a square tower where the owner of all this land lived—a reclusive count who also owned the farmhouse I rented nearby, on the outskirts of the village of Vignavecchia. The tombs I was going to visit that day were part of the tower estate, and I had been told that I should apply there to request official permission to photograph them and arrange for a guide. I had come to this remote corner of Italy to research Etruscan sites…

Pre-order of the 20th anniversary edition now available from PLEASURE BOAT STUDIO BOOKS The print & ebook will be available online & in bookstores everywhere in Sept.2024.

Thanks, Linda. I was dazzled by The Etruscan when it first came out and appreciate the thoroughness of this posting in providing background for another encounter. I hope the new edition will also attract new readership drawn by the magic of the Etruscan culture, so mysterious still today, almost wholly left to its commentators (you, Lawrence) as they contemplate the various ‘doors’ the Etruscans left for them—all better than science since providing insight into creative imagination.

I just recently visited Tuscia and some of the painted tombs in Tarquinia and was surprised to see "La Chimera" showing on my ITA flight back to NYC. What a pleasure to watch the film having just spent several days in that beautiful territory. The Etruscan sounds like a fascinating story!