Like many people all over the world, I have long suffered from islomania – a disease first cited in Lawrence Durrell’s Reflections on a Marine Venus where the author claims that his friend Gideon discovered the term in a medical textbook. “Isolmania,” Gideon explains, is “an affliction of the spirit.” He goes on to say “There are people…who find islands somehow irresistible. The mere knowledge that they are on an island, a little world surrounded by the sea, fills them with an indescribable intoxication.”

Since my first ferry ride to Sanibel Island (back then not yet connected by a bridge to the swampy Florida mainland) at the age three, I have been fascinated by the otherness and “elsewhereness” of islands and continue to experience a sense of dizzying delight whenever I find myself awash on a speck of land in the middle of the ocean. I love islands’ vulnerability to weather and wind and the rewards they bring to those who hold on throughout the rougher seasons. Above all, I love the wholeness of islands and their self-contained compression like seeds which hold within a blueprint of the entire universe.

As the site of shipwrecks, exile, and transformation – islands tease our imagination into believing we can live outside time.

For many years, I have been a collector, if not of islands, then of island experiences, and of postcards, seashells, maps, and ferry tickets attesting to my brief visits and longer sojourns on island shores: Nantucket, the Aegean islands, the Dodecanese, the Pontian archipelago, the Maddalena archipelago, theAeolians, and many more. This substack is accompanied by a free audiobook of a short story, Mal d’Isola, set on the loneliest of Aeolian sisters. In the upcoming weeks, I will be dedicating my substack pages to island explorations.

In addition to the audiobook, arriving in a separate post — here is the first installment of my Islomania pages.

An Island Library. Crete 1978

I sit writing by lamplight in a cool, whitewashed room overlooking the scattered cube houses of a Cretan fishing village. The lantern casts its yellow cocoon of light in the darkness, mapping the rough walls with giant, flickering silhouettes. From the kafeneon below comes the rhythmic thumping of a generator, overlaid with tinny blasts of music as the same songs are played over and over into the night. I know enough Greek to recognize a few words: ‘S’agapo’ … I love you. ‘Tipota’ … nothing. ‘Allou’ …elsewhere, somehow these three concepts cohere to make a complete if elusive meaning, at least in my recent experience. It is August 1978, and I am recovering from a personal shipwreck.

Towering bookshelves surround me, crammed with paperbacks, belonging to my friend, Teresa, an artist, who married a Greek fisherman and recently moved to this remote outpost. She shipped these books over from Florida, to remind her who she is and where she has been, vital in a place like this where a reluctance to budge creeps into your limbs once you finally arrive. It takes hours to climb back up to the lonely bus stop along the National Road. The only easy escape is by boat or by book, of which here in this room, there are many.

I have been living in Rome on meager means, traveling about for weeks now to places where books in English are mostly unaffordable. Teresa’s library is as enchanting as Prospero’s cell where the banished Duke of Milan kept his magic books. With their sand-scattered pages, their print blurred with damp, their sharp smell of mold, these paperbacks are no less precious than Prospero’s leather-bound grimoires, each conjuring a universe of its own, abundantly providing the one thing so necessary to island life: good conversation in a familiar language.

When the generator runs down after midnight, the village sinks into silence. Sea and sky are pitch black, indistinguishable below the froth of the Milky Way. Too restless to sleep, I pull a book from the shelf. It’s an old friend -- Justine, vol. I of Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet. Sea air isn’t good for preserving books. Justine’s cover has buckled; the brittle corners of its pages break off as I leaf through it, looking for my favorite passage: “The sea is high today, with a thrilling flush of wind. In the midst of winter you can feel the inventions of spring..... I have escaped to this island with a few books and the child.”

There I was, in the fullness of summer at age 25, dreaming of wintering on an island, so that I could write a book. This ideal of writerly retreat and exile would linger in my mind for four decades, and still echoes from time to time: If only I could get away and live the life I imagined lay within those lines. Someday, I thought, I would make that fantasy real. What I didn’t understand was that I was already living it, right then, at that moment. That room with its musty books, that semi-deserted village, that island visited for a short summer were as close as I would ever get.

During that summer in Crete, I helped Teresa with her household chores. We washed tar-spotted jeans and faded sheets by hand in a tub, wringing them out till our forearms were numb from the effort. We harvested chickpeas, plucking them one by one from their pods, and carried prickly green sheaves of fodder to her goats. We discussed Minoan goddesses, herbal cures, Greek verbs and Greek men. I learned to crochet lace and to make fish soup. I swam through dangerous currents to a small island where a ruined Minoan palace was under excavation and brought back forbidden pottery fragments concealed in my bikini top. I sat for hours on the cement floor of a mountain chapel, inhaling the sweetness of beeswax tapers and wondering what to do with my life. At night I sat in my room and read through Teresa’s library, volume after volume by lantern light, jotting desultory notes in a journal.

In early September as my own visit was drawing to a close, a pair of German intellectuals arrived, occupied the only free room in the village, and spent days on end in the kafeneon, taking turns, hammering away on a portable Olivetti 22. These two were real writers, I was told. How I envied them. I was sure that if I could just take a few more months off and come here to live, I’d be able to finish the novel I had started ages ago. Other people did it. They just upped and left their jobs, cleaned out their savings at the bank, and struck out for exotic locales. Couldn’t I do that too: live simply on an island, surrounded by books, and write?

“It’s not a good idea,” Teresa countered, when I confided my dream to her over coffee at the kafeneon. I already had my eye on a couple of uninhabited houses located in the outskirts of the village. One house, perched above a secluded cove, had a spacious terrace overlooking the sea, shaded by a riotous pink bougainvillea, and a staircase zigzagging down the cliff to a private beach. “There’s no plumbing out there,” Teresa warned, “Without a car, how would you transport your drinking water? “ The other, built high on a promontory facing west, was a favorite destination of mine for hikes at sunset, but it was a steep climb up through a forest of razor-sharp thorns, shunned even by goats. “You can’t be serious. Nobody can live up there. Besides, you’d be alone. People in the village might get the wrong idea. Anyway, the men use that house up there when they want to get away from their wives.”

In mid-September the weather turned unexpectedly rough. The sirocco swept through the village after midnight, whistling through cracks, crashing bottles of raki from shelves to the ground, unhinging doors. In the morning, a yellowish veil tinged the sky and everything was coated with a layer of tawny, African sand finer than confectioner’s sugar. I watched the gloomy-faced fishermen tug their boats out of the water in a poorly-coordinated, heave-ho dance onto the shingled beach. It was time to go. “Come back at Christmas if you want to know what it’s really like to live here,” Teresa suggested as I packed up my stuff. She handed me her paperback copy of Justine for me to read on the three- day- trip back to Rome. “You can bring this back to me when you come.”

I never made it back in winter time. In the rainy autumns that followed, I’d find myself staring at the curdled Roman twilight through the greasy windows of a crowded bus stalled in traffic, wet umbrellas of the other passengers poking my ribs. From the bus stop, it was a short walk home, where I’d fix myself a bowl of chicken soup and a poached egg to ward off an incipient cold, consumed while leafing through a pack of English compositions to be graded by morning. With my stockinged feet poised on the tepid radiator, I kept thinking about that book-lined room by the sea and dreamed of the books I would have read there and especially, the ones I would have written.

Several years ago, closing up the flat where I had been living before moving to another area of Rome, I found that copy of Justine, borrowed from Teresa’s library, which I had never sent back to her. She had divorced her fisherman and had left Crete by then. Her cell with its bookshelves had been dismantled, the building torn down to make room for tourist flats. Some of her books had been sent back to the USA; others given away to the newcomers in the village all eager for a good read on a winter evening or a vintage 1970s vegetarian cookbook. Still others probably ended up in somebody’s charcoal stove.

In the flurry of moving, I too found myself discarding boxfuls of paperbacks I had sent or brought from home fifteen years earlier when I had moved to Rome, now too ragged to even give away. Justine was in dreadful condition, a sheaf of loose yellow papers, held together with a stiff rubber band. I had lost touch with Teresa and no longer had her address, so I couldn’t send it back. With misgivings, I added Justine to the pile to toss out. It was time I put an end to that fantasy, living in a little house with books on a Greek island. Yet I felt sad as I carried the box out to the street and put the books near the trash bin. I had just dumped a good chunk of my life and of my aspirations. I went back up to contemplate the empty shelves of my flat as I drank of a cup of tea, then on impulse decided to go back down to the street and rescue my copy of Justine. Someone else had claimed it though. The book – but only that one – was gone. The dream had been passed on.

End

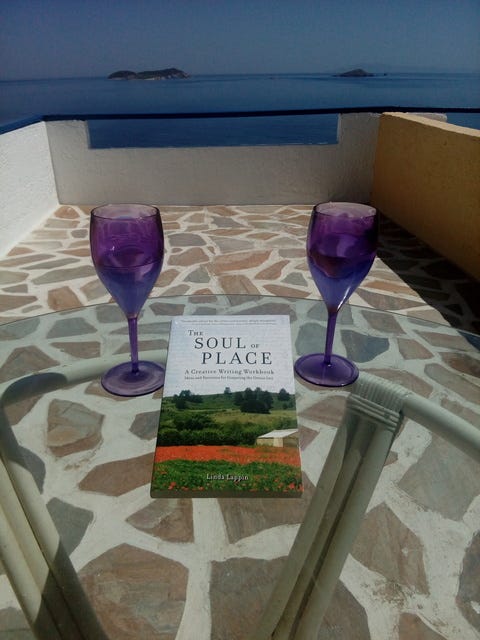

For my philosophy of place-writing, please see The Soul of Place: Ideas & Exercises for Conjuring the Genius Loci

Please see audio: Mal d’Isola - the loneliest of the Aeolian sisters for a free audiobook.

Mal D'Isola -

To accompany this week’s substack dedicated to “Islomania,” I’ve included a 33 min. audiobook of my short story Mal d’Isola. It will take you on a trip to Alicudi, the loneliest of the Aeolian sisters. “An hour later they reach their destination: Alicudi, the last island in the chain: a blackened cone with a narrow lip of purplish boulders along th…

I have tears in my eyes. My very first real vacation as an adult was with you in Mochlos. I think in 1984.

Oh... this is lovely!