I don’t know why exactly but gothic novels — in the traditional meaning of the term— have always fascinated me: Wuthering Heights, The Castle of Otranto, the gothic elements of Jane Eyre, or the more modern twists and turns of The Magus. I have often wondered: what is it about the gothic that resonates so deeply in my imagination? Perhaps it’s the symbolic architecture — dilapidated mansions with odd-shaped rooms, bewildering corridors and crypts, labyrinthine gardens—all representing distorted fears and longings. Or perhaps the sublime landscapes of looming mountains, canyons, brooding seas far from civilized society where these unheimlich habitations are set. Or maybe it’s the intrusion of past secrets upon the present; the explosion into the Now of something long lost or buried. Or the power of a work of art — like a sculpture garden — to communicate an artist’s nightmare across centuries (as in my novel Signatures in Stone). Or as in The Etruscan, it might be the mysterious, mesmerizing power some individuals hold over others— particularly women ( but not only: see The Magus) - a power that springs from that archaic, non-rational part of ourselves that Jung called “the shadow.”

Some years ago, I came to know an area of Italy which fed this fascination of mine for the eerie, uncanny, unheimlich. I found that nourishment in ruins abandoned in the countryside — in step pyramids predating the Etruscans and medieval towers and castles cobbled together over centuries filled with neglected artworks, mildewed tapestries, and opaque mirrors peering into the impossible. In tunnels burrowing beneath humble villages, ending in windowless, underground rooms where safety was once sought - or perhaps privacy for secret rites. I found it in thousand-year-old silver figurines dug up from the red earth, in twin-tailed mermaids guarding tombs and in stone giants pointing the way to the Underworld.

This being the month of mystery, of falling and decaying leaves, of fruitfulness and fires in the mist, journeys to the netherworld —I’ll be dedicating a few posts and audio readings to Gothic in Tuscia…

For more than thirty years, I have divided my time between Rome and a village in the Tuscia Viterbese – an area north of Rome once inhabited by the Etruscans, and later chosen by noble Roman families of the 16thand 17th centuries for their summer residences. Tuscia, the northern tip of the Lazio Region bordering Tuscany, is an area of stunning natural beauty, with gorges and canyons, massive rock formations, geothermic activity, hot springs and volcanic lakes, thick woods teeming with wild boar and porcini mushrooms. Every hilltop boasts a quaint medieval tower, castle, church, monastery, or Renaissance villa. This is Etruscan country, celebrated in Alice Rohrwacher’s recent film La Chimera, and in D.H. Lawrence’s famous book: Etruscan Places. Etruscan and pre-Etruscan ruins and sacred sites are scattered everywhere: many just out in the open, in isolated places in the countryside, in the middle of woods or on abandoned farmland for you to explore at any time of day.

Another feature of this unique area is its formal gardens, created by Renaissance and baroque architects for their noble patrons. These are esoteric story-telling gardens, designed to tell a story through pathways, plants, statues, and symbols—and in some cases, to create positive astrological influences that might help change a negative fate. One of the most famous of these gardens/parks is the Park of Monsters, also known as The Sacred Wood, of Bomarzo, created in the sixteenth century by the Italian nobleman, Vicino Orsini, as a memorial to his wife. 2023 marked the five hundredth anniversary of his birth.

This park is unique in many ways among Italian formal gardens. Firstly, it is populated with a legion of giant, grotesque, hallucinatory sculptures depicting monsters, gods, imaginary beings of every form, including the Hell Mouth, the most famous of its sculptures which has served as an inspiration for dozens of buildings, doorways, and stage sets.

Secondly, nearly all these sculptures have been carved in boulders and rock formations in situ without those stones being cut, uprooted or removed from the spot they emerge from the ground. This is an important detail as in the sixteenth century, it was generally believed that stones “grew” in the earth like teeth and bones in our bodies, and that a quarried stone was, essentially, “dead.” Thus the stone sculptures in Bomarzo retained their organic link to the earth, and were still “alive.” Thirdly, no one knows who provided the original designs for the sculptures (although there are many theories), and lastly, no one knows exactly what the whole design actually means.

Everyone who visits the place comes away bewildered , for the Sacred Wood clearly has some meaning that we no longer have the key to understand. Of course, that is what Vicino wanted, to create a sense of awe and the supernatural in visitors to his park. But he also wanted them to make the effort to decode the message he had planted there, and for this reason he put inscriptions along the pathways to guide visitors along. Still, after centuries, the Sacred Wood eludes interpretation. Tomes have been written explaining the individual sculptures and their composite meaning. There is a general consensus that the park represents an itinerary of self-knowledge connected to the figure of Persephone/Proserpina—the lost child at the heart of the ancient Eleusinian mysteries.

In this reading of the park’s meaning, the visitors must make a journey through the underworld, undergo a series of trials and tests in order to face up to their own darkness, obsessions, illusions, fears – what Jung called “the Shadow” -- manifested by the monstrous statues. Its whole point was to lead the visitor down into hell in search of rebirth, as in the myth of Demeter and Persephone.

This myth underpins the plot of my novel Signatures in Stone: A Bomarzo Mystery. In my novel, crime writer Daphne DuBlanc comes to Bomarzo with other artists to write a new book, but ends up as the prime suspect for a murder that takes place in the park. Daphne has a theory that by reading signs or “signatures” scattered all around us, we can uncover hidden truths and even predict the future.

“We are constantly immersed in a network of signs and symbols, whose meaning eludes us, but which, if only we could read them, would reveal every detail of our past and even predict our future. The mind talks to itself not with words, but with scrambled symbols, pictures, fragments, often severed from any literal meaning. If we wish to learn to read them, we must abandon the rational links of words to thoughts. Signatures are always there waiting for us, like unopened letters slid beneath the front door, accumulating after a long period of absence, written in a hieroglyphic alphabet we have forgotten.” Signatures in Stone —

The character of Daphne is very very loosely based on Mary Butts, an English writer of the twenties, who has written some very beautiful but little known works of fiction and nonfiction, who had a passion for occult philosophy. Her notebooks discuss a theory of signatures, or correspondences, according to which every sign in the outer world points to a meaning in the inner world, an idea developed by Swedenborg. Daphne adopts this concept when attempting to solve crimes. – and she comes to view the statues of the Monster Park as signatures of their creator’s interior world.She’ll have to use her extraordinary intuitive gifts and sleuthing skills to save her skin and solve the crime, and in doing so also will also discover the secret of the Park of Monsters – and its destructive and redemptive power over all those who wander there.

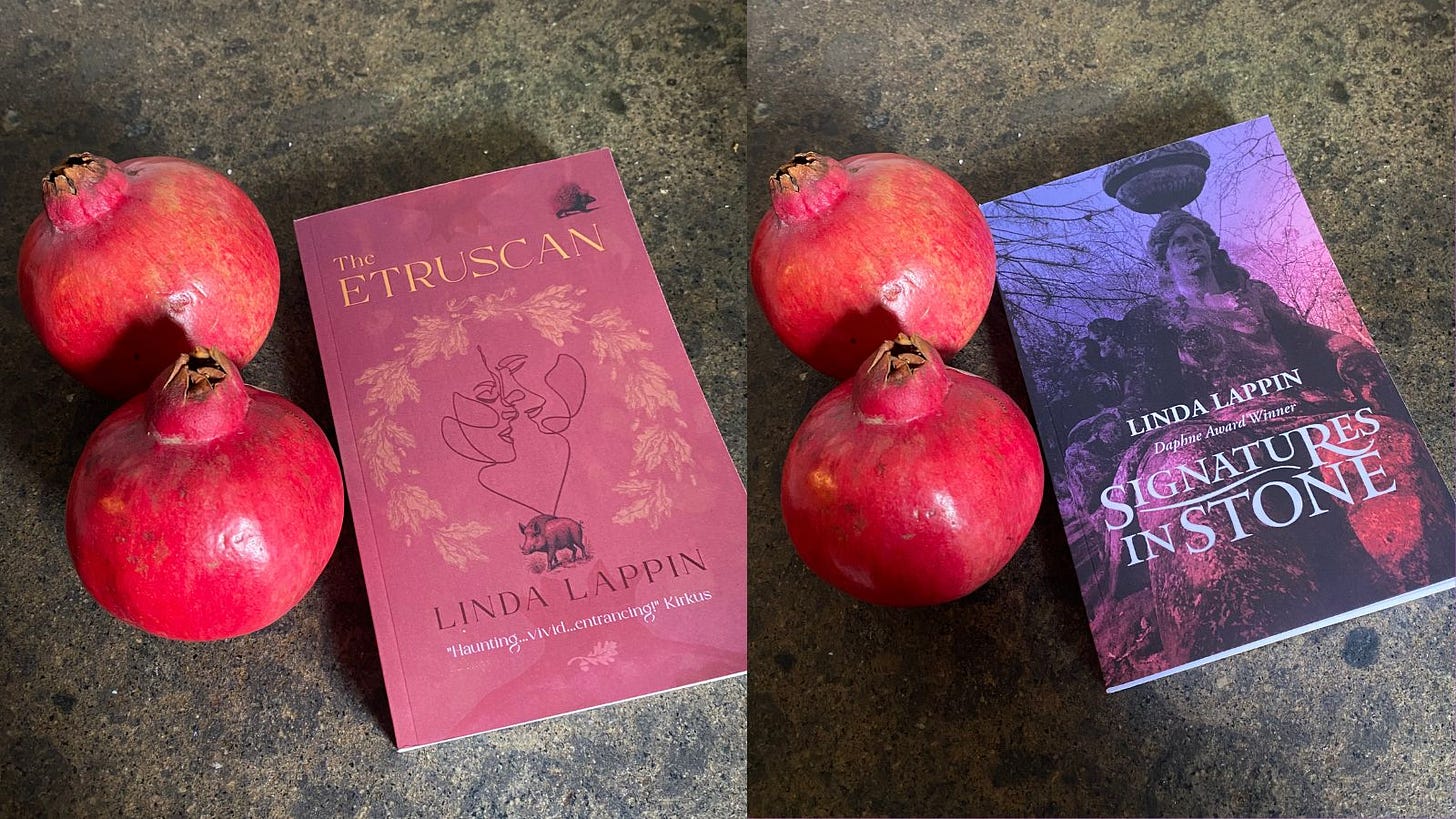

My gothic novels: Signatures in Stone: A Bomarzo Mystery

in paperback from Pleasure Boat Studio; distributed by Ingram, available through Amazon, BN, Bookshop, on all ebook platforms, and on Hoopla & Overdrive. Cover designs by Lauren Grosskopf

Thanks for visiting. Do share this with anyone you think might enjoy it.