A visit to the studio of Justin Bradshaw

Acclaimed British Artist Working in Italy for Three Decades

We’d heard the road was daunting in rainy weather, so we waited for a dry day before visiting artist Justin Bradshaw in his studio near Corchiano. Ignoring the “Divieto di Transito” sign, we followed the artist in our little Aygo as far as it would go – but when it tilted dizzily up on one side as we rumbled along a deep rut in the mud, we had second thoughts. Pulling over, we scrambled out and piled into our host’s car to complete the journey. It was Easter Sunday. It had taken months to organize this outing. But once we’d finally made it, it felt as if we had skipped way back in time.

This flat green sea of fields and weeds used to be tobacco country. A train once stitched through this countryside, all the way from Orte to the port of Civitavecchia, calling at the now shuttered Corchiano station. The line ceased operations in 1994. We’re far from any grocery store, shop, or café, from paved roads or streetlights. No noise, crowds, traffic, or distraction – and that’s the way this London-born artist likes it. It’s a miracle that cell phone signals reach out this far – and it’s a blessing that they do.

Bradshaw’s studio occupies the ground floor of a nineteenth century, two-story farmhouse perched on the edge of a deep, wild ravine. A sturdy pergola covers the terrace outside the entrance. An old blackened wood oven in disuse gapes on the front. Decades ago, the place was renovated with electricity, plumbing, kitchen, bathroom, heating, providing basic comforts, but little more.

A fire is blazing in the hearth as we step inside to find a lovely table laid for lunch. Double doors of a giant picture window look straight over the ravine- but it’s too windy to open them today. On cooler days, thick mist rises from the ravine, blurring the windows with white. At night boars come close to the house, snuffling right outside the door. In early summer, nightingales enchant the evening air. It’s a place truly out of time.

Self-exiled from London to Italy in 1994, just out of art school, Bradshaw paid his way to Rome by working at a Salvation Army hospice for the homeless. He soon fell in love with the Eternal City and its ancient stones washed with history and neglect. He began with watercolors, painting in the street, retracing the 18th century sketching itineraries of the Grand Tour. And there in the street, he was discovered by Roman antiquarian Carlo Sestieri, who became his patron and mentor, introducing him to the history of Roman culture, and helping him financially.

Thirty years on, Justin Bradshaw has made a name for himself as a figurative painter of extraordinary gifts and amazing skill, receiving high praises from Vittorio Sgarbi, Italy’s most eminent (if eccentric) art critic. While deeply entrenched in the classical tradition, influenced by Rembrandt and by the Flemish school, Bradshaw’s work is often spiked with quirky wit, and sometimes dark humor.

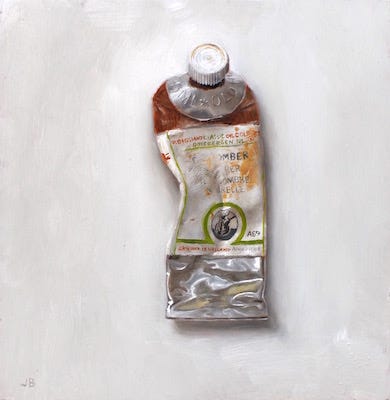

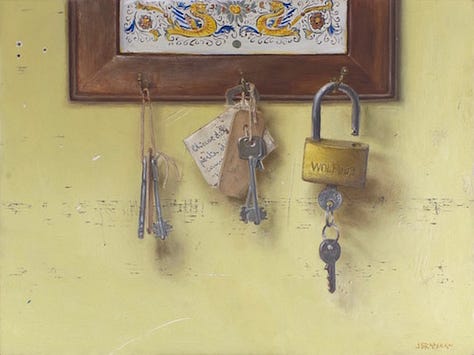

Bradshaw’s website divides his work into four categories: Things – this is the bread and butter of his production snapped up by collectors as soon as they’re available.

Small, hyperreal, witty renderings on copper of everyday objects: an empty bed with rumpled sheets; rings of lost keys; mangled paint tubes; a half-peeled banana; perky, whittled down pencils; a bread roll with a bite taken out of it, a frothy wedding dress without its bride, a crumpled bar bill. Aside from their wit, these objects also speak of absence and loss in varying degrees of intensity. They are talismans of time passing. Floating detached in their own dreamlike space, some are so astonishingly lifelike, you could pluck them from the picture and carry them away.

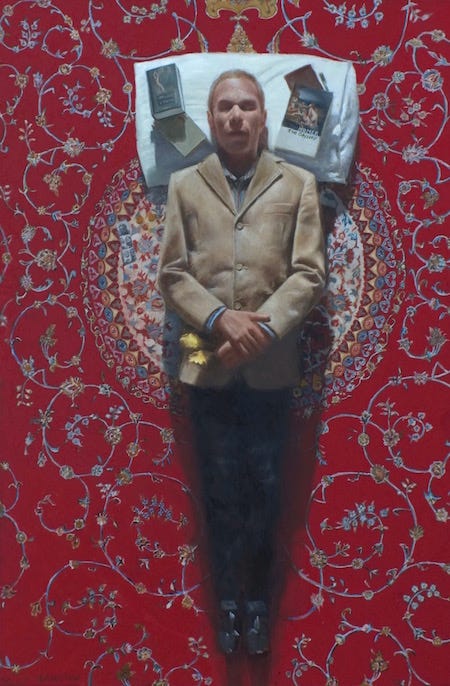

A second category, Actions, comprises contemporary remakes of mythological, literary or religious subjects with friends and neighbors posing as gods, saints, historical personages. These paintings have a Caravaggio-esque vibe gone pop, infused with bizarre humor. An insouciant Salome in denim hot pants brandishes an ice cream cone. Voluptuous Teresa of Avila lolls about in a magnificent disarray of billowing bedsheets, and Bradshaw himself as a corpse is laid out on a Persian rug/ magic carpet with a copy of The Odyssey by his head.

Then there are the serious portraits in the third category People, held by prestigious public and private collections.

With their masterful technique and psychological insight, they show his debt to Rembrandt, while his own wolfish, unsettling self-portraits offer homage to Lucian Freud.

The last category is Works on Paper, a favorite for collectors of classical tastes showing his Roman roots: picturesque scenes of Rome and its environs, monuments and ruins drawn with goose quills. These are enveloped in an eerie, dreamlike atmosphere, both enticing and forlorn, where volumes seem strangely elastic and unreal.

In these we see his obsession with the passing of time. In all four categories, we can understand what Sgarbi meant when he praised the extreme virtuosity of Bradshaw’s technique – and his main desire “vuole stupire.” He wants to astonish us.

In many ways, Bradshaw is a man from another time. He makes all his brushes, quills, and paints himself, following traditional methods and recipes collected by Cennino Cennini, author of the 15th century guide to painting, il Libro dell’ Arte. He now uses only natural pigments, and has often compared the process of painting to alchemy. Unattached to any educational institution and with loose ties only to a couple of galleries, he makes his living selling his work to a small but ever-expanding circle of collectors. Still, it’s a struggle for survival and an extreme choice. Each work is preceded by a phase of meticulous research, which means there is also a great time commitment invested in every piece he produces.

Our Easter lunch consists of fava beans and pecorino, a frittata with wild asparagus gathered from the yard, an artisanal colomba, the traditional Easter cake with almonds. A big black foundling dog who just showed up one day sits composedly at our feet under the table. Conversation turns to alchemy and its relation to painting and to pigments. One of the guests asks – “Couldn’t you make more paintings more quickly if you bought your paints?” – To which the artist testily replies: “But it’s part of the whole process!” Picking out a phial of bright blue powder he says, “I challenge to find a tube of paint with this exact color! Take five years, Take ten. You won’t find it.”

Just inside the door a low table displays jars of his goose quills and handmade brushes. On the opposite wall, a small alchemical cabinet of his natural pigments. A dozen Thing paintings and studies are propped on the mantelpiece; more are taped to the walls, including his recent “Unmade Bed” series.

A corridor leads off this main room to a series of smaller rooms. One is a laboratory where he prepares his paints, while in two other rooms, scenes have been set up for his models. In one we find a headless mannequin in a colorful suit and other clothing items on hangers; in the other, the rusty bedstead, with mattress and rumpled sheets, now the focus of a current series.

A bed stark against the back wall covered in black, strong light streaming in from the only window, this arresting scene is a theater set—where the actor is momentarily absent. Once you have entered this magical space, you have the uncanny feeling of straying into one of Bradshaw’s paintings.

One of my favorite paintings by Justin Bradshaw is: Jeanette’s Desk, in memory of Jeanette.

.

The chair is empty, the writer has gone, but the light on her desk has been left on, illuminating an unsent letter or card. In the empty blue stillness, we sense her presence. We can almost see her bent over her desk, with the peaceful precision of Vermeer’s Lacemaker, writing to loved ones, family – a testimony of her days threaded one on the other. Our eyes are attracted to that unsent card whose journey has not yet begun. And as our attention is drawn in towards the small, secret space of the card, we are startled to meet the artist’s blurred gaze in the round mirror handing directly above it. The mirror in turn casts a gauzy luminescence on the floorboards, in the very spot where she might once have stood to adjust her hair before going downstairs to welcome a guest. The door is open. She has just stepped out.

Please join me here on Substack - where I’ll be posting about my Italian life, books, workshops, art, travels, friends, food, reviews, and dreams. More news about a workshop with Justin Bradshaw is forthcoming.

As usual, beautiful and transporting! I look foward to the next one! ❤️

wonderful, shared with my lists, media